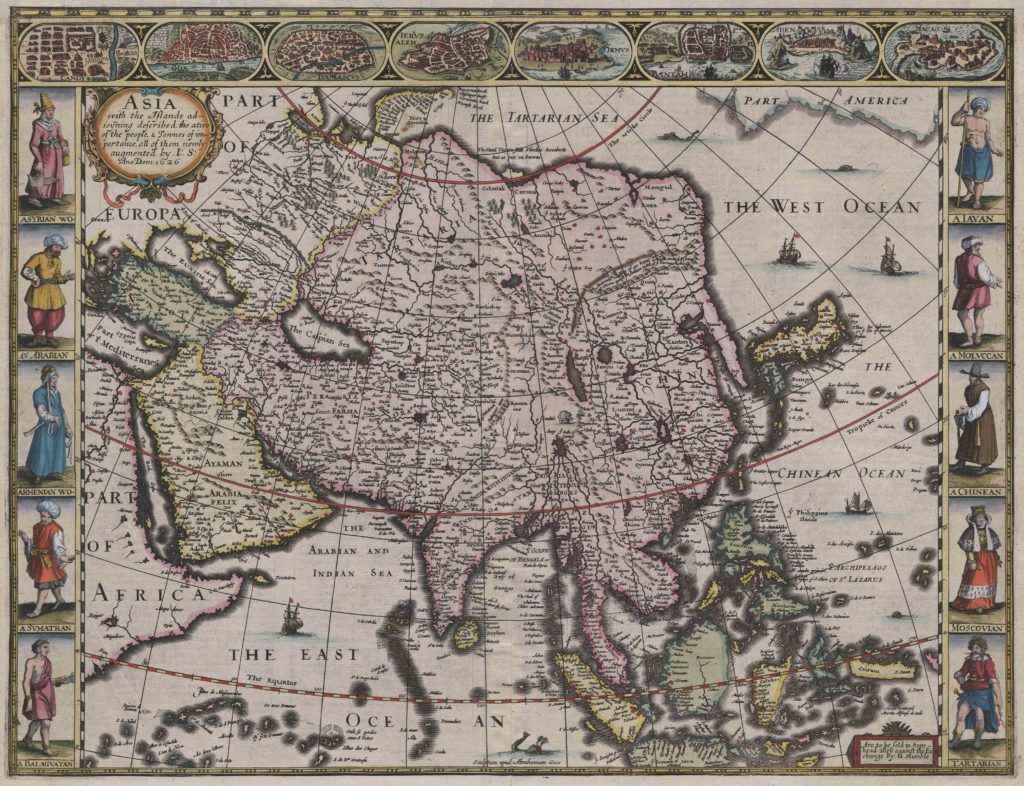

This engraving, later hand-coloured, was originally issued in London as part of a series called A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World by the cartographer John Speed (c. 1552–1629). Speed was an artisan scholar, and very much a figure of the early modern age. He trained as a tailor, but he was also an antiquary, geographer, and historian, best known now as the author of a 1611 collection of maps called The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain. Speed published the Prospect with a reissue of Theatre, thereby linking the national and the global, and this two-part work continued to be reprinted long after his death. The Asia map has been signed along the bottom by the engraver, Abraham Goos of Amsterdam: ‘Sculptum apud Abrahamum Goos.’ Another inscription records that the map was to be sold in London by G[eorge] Humble at the sign of the White Horse in Popes Head Alley, near the present Bank of England.

The map is a record of contact and exchange both scholarly and mercantile. The links to seventeenth-century travel and trade can be seen most directly in the eight views of Asian cities along the top edge and in the ten costumed figures along the sides, which provide a pictorial gloss on the geography. The city views came mostly from a single source, the Civitates Orbis Terrarum of Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, first published in 1572. Here they are roughly grouped not only by region but also by date of European awareness or contact, from ancient history into the seventeenth-century commercial world. Apart from Jerusalem, all the cities pictured were major ports of seventeenth-century trade: Damascus, Hormuz and Aden on the Persian Gulf, Goa in southern India, Candy (Sri Lanka); Bantam (now Banten) in Java, and Macao on the South China Sea.

Most of the costumed figures can also be linked to major trade communities. From the top left, they are labelled as an Assyrian woman, an Arabian man, an Armenian woman, a Sumatran man, and a ‘Balaguatan,’ — an inhabitant of Balaghat, the state around the port of Goa. Along the right, the rough grouping by time and space reverses: a Javan man, a man from the Moluccas, a ‘Chinean’ or Chinese man, a ‘Moscovian’ woman, and a Tartarian, or Mongol. The original sources for the costumed figures were diverse. They included Hans Weigel’s Habitus praecipuorum populorum (Nuremberg, 1577); the prints of Sebastian Vrancx, known as the Variarum Gentium Ornatus, and a single figure (the Tatar) from Enea Vico’s Diversarum gentium nostrae aetatis habitus (Venice, 1558).

The Prospect is often considered the first world atlas to be created by an English mapmaker. Yet, like many maps in the series, Speed’s Asia map is closely based on an earlier model, in this case a map of Willem Jancz Blaeu of Amsterdam, issued in 1617. The Dutch inscriptions have been translated and truncated in some cases to fit, as with the Armenian and Assyrian women, but otherwise retained; Speed also cut one of Blaeu’s cities (Calicut) and included only one of each pair of Blaeu’s costumed figures. Blaeu had in turn depended closely on the Atlas of Mercator published by Jodocus Hondius, who is also credited as the first to add small vignettes of cities and figures to the borders of such maps. Reusing the plates was a cost-saving measure in a commercial venture, but this map is also a record of a series of friendships in a relatively small community of amateur merchant-scholars: among other links, Hondius had collaborated with Speed when he was exiled in London from 1584 until 1593.

Anne Dunlop, University of Melbourne