F O R E I G N B O D I E S

At the root of any idea of foreignness is basic, physical exteriority. The modern English ‘foreign’ derives from the Latin fores, and marked the fact of being on the other side of a door. The word first appears in the thirteenth century as ‘ferren’ or ‘foreyne’ with this sense of something physically outside. Calling something foreign always implies an idea of belonging or exclusion. It always begs the question, ‘foreign in relation to what?’

Defining foreignness – who belongs and who doesn’t – is a major contemporary issue, but the problem is not new. It has always been linked to ideas of the ‘proper’ or natural place of human beings. Ancient writers like Aristotle had offered theories of climate to explain differences in human customs and character. Christian Europeans believed that all humans descended from Adam and Eve: in his book De Civitas Dei (The City of God), Saint Augustine (354–430) argued that the Antipodes could not be inhabited since it would have been impossible for these descendants to have travelled to the other side of the world across unknown waters. A further belief was that there were three continents, Asia, Africa, and Europe, peopled after the Biblical flood by the descendants of Noah’s three sons. Faced with the ‘newly discovered’ peoples of the Americas, sixteenth-century Europeans debated whether they were human or not, an issue not fully resolved by Pope Paul III’s 1537 proclamation that they were (and should therefore be converted to Christianity by their conquerors).

This exhibition is focused on objects from about 1400 to 1700, mostly but not all made in Europe. Its goal is to explore how such early modern images and objects constructed the foreign, the exotic, and the other in this period of intense social and artistic change – marked by the rise of cities and increasingly centralized nation states, European exploration of the world and colonization of large parts of it, free and forced mass migrations of peoples, and newly globalized trade. In this moment of new and intense mobility, objects were also as migrants; they were made of commodities and designed to be exported, imported, and traded. Such objects moved and keep moving, now virtually, and in the process they can say something about people who have collected them or places they have come from.

The exhibition has grown from a 2016–2019 team research project led by Anne Dunlop of the University of Melbourne and Cordelia Warr of the University of Manchester. The project, ‘Connecting Collections,’ was inspired by the extraordinary early European art collections in the two cities. The goal has been to encourage collaboration across the two campuses, and to act as an incubator for new research. The authors range from full professors to students in early stages of MA and PhD research, and they have come from all over Australia and the U.K.

To explore foreignness and object culture, our team has chosen three themes: Global –Local; Monstrous – Marvellous; and Bodies – Inside & Outside. Each theme is intended to highlight a different kind of foreign body, a different relation of interiority and exteriority, belonging and exclusion. The most obvious might seem the opposition of Global – Local. A newly global world is one of the defining features of the early modern age, with peoples all over the world in contact as never before, and seeking to define themselves at least in part in opposition to others.

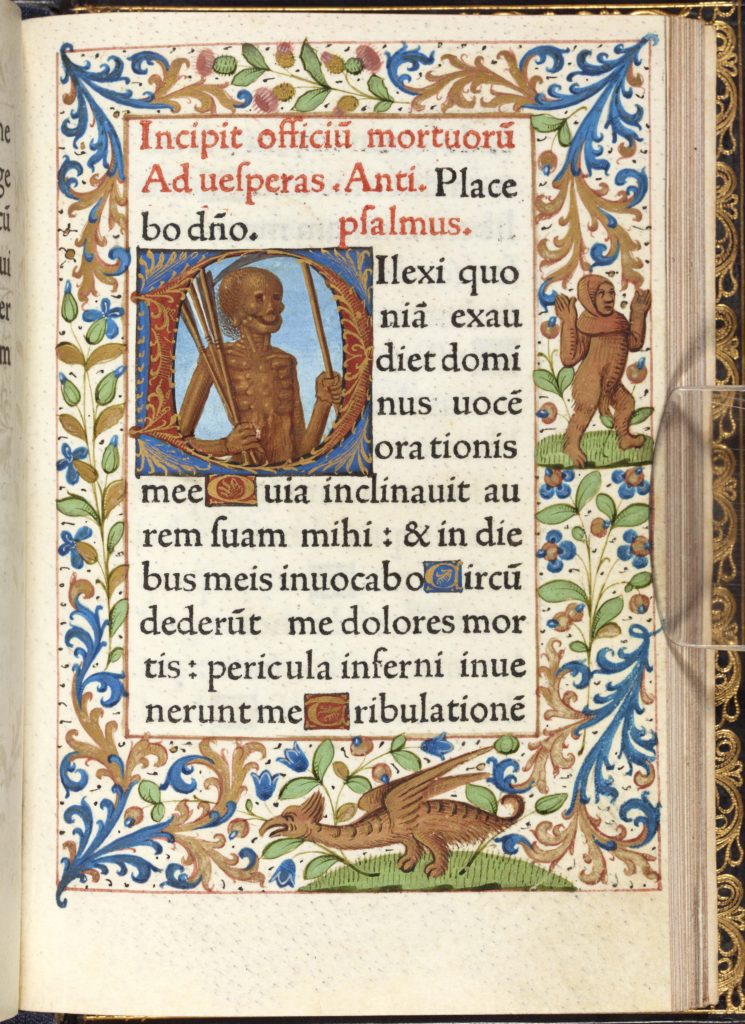

Monstrous – Marvellous is related to this: ideas of the grotesque or the exceptionally beautiful, and redefinitions of the human grew from expectations of what was normal, local, and shared. These dichotomies were marked by the duality of attraction and repulsion: an image of a caricatured old woman or an American cannibal could both repel and call the curious. Class, gender, sexuality, and race might be at stake, as behaviour could also make the monstrous, an issue also at stake in the last category, Bodies – Inside & Outside. This category is linked to the medical idea of a foreign body or a foreign object, something embedded but not proper to the body as a whole. It also, however, points to the fact that bodies or parts of bodies could be made foreign to themselves, as the skin of an inner arm might be grafted to make a nose, a procedure shown in one print here – every normal body is a potential monster or marvel in waiting.

Anne Dunlop, University of Melbourne