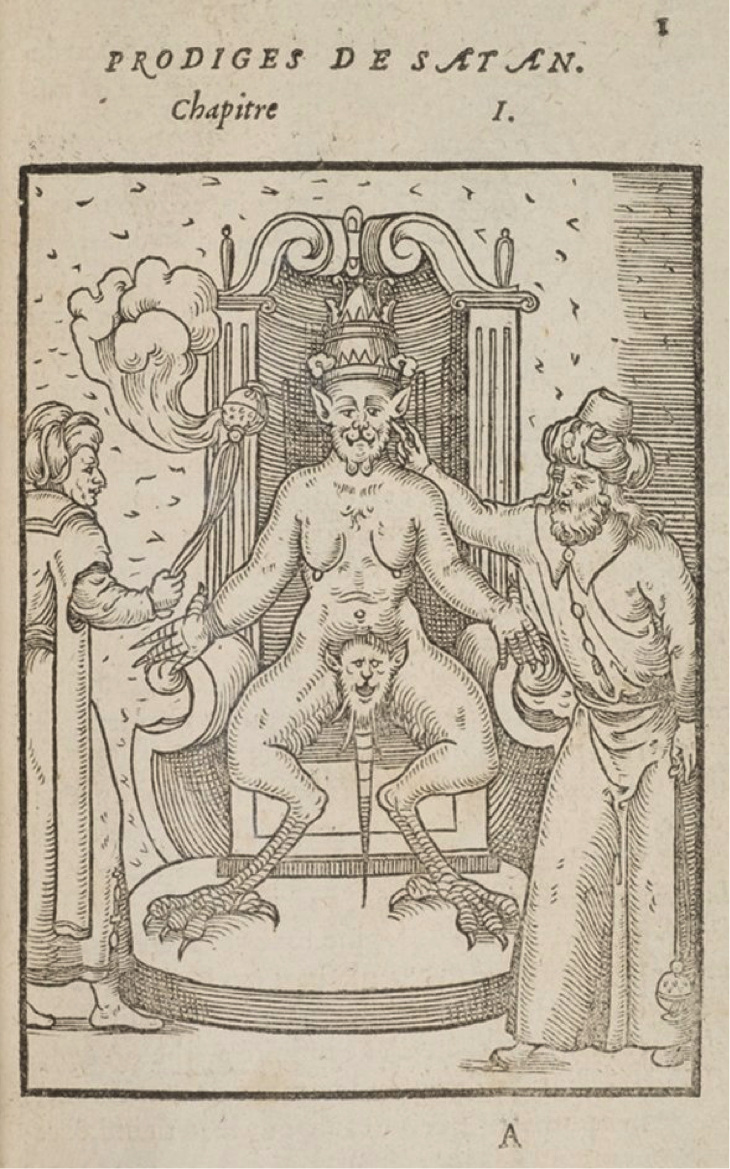

Title: ‘Prodiges de Satan’ (Prodigies of Satan), Pierre Boaistuau, Histoires prodigieuses, extraictes de plusieurs fameux autheurs, Grecs & Latins, sacrez & prophanes : mises en nostre langue par P. Boaistuau, surnomé Launay, natif de Bretagne : avec les pourtraicts & figures (Historical wonders, drawn from many famous authors, Greek and Latin, sacred and secular, translated into our language by P. Boaistuau, called Launay, of Brittany, with images) p. 1

Place: Published in Paris by Hierome de Marnef and Guillaume Cavellat

Date: 1566

Medium & technique: Woodcut on paper

Dimensions: 160 x 110 mm

Themes: Monstrous – Marvellous

Collection: The University of Melbourne Rare Books Collection, UniM Bail SpC/RB Call No: 39A/19

Pierre Boaistuau, born in Nantes around 1517, was a French humanist writer. One of his most popular books was the Histoires prodigieuses. It is classified as a ‘wonder book’, an increasingly popular literary genre during the sixteenth century containing stories describing demons, monstrous births and tales of natural phenomena. This woodcut is an early reprint using the same woodblocks, made by an unknown engraver, found in the first edition from 1560. Entitled ‘Prodiges de Satan’, it is the first and one of the most dramatic images from the book’s 49 woodcuts. Depicted with arms spread is the enthroned devil, waited on by attendants who swing censers, venerating his monstrous form. His body is a dual-gendered, half-human, half-beast hybrid, with the face of a lion, feet of a cockerel, and webbed hands and tail. The image is based on European visual depictions of the ‘Devil in Calicut’. This devil was an ‘idol’ in the coastal town of Calicut in the south Indian state of Kerala, described in earlier written travel accounts, including those by the Italian traveller Ludovico di Varthema, published in 1510. The image of the ‘Devil in Calicut’ was probably a misinterpretation of the Hindu god Narasimha, the man-lion avatar of Vishnu. Produced in the early years of the French Wars of Religion, the ‘Prodiges de Satan’ woodcut suggests how such foreign religious customs encountered by European travellers could be adapted to warn readers of the more local threat of heretical beliefs in France during the later sixteenth century.

Susie Chadbourne, University of Melbourne

Further Reading:

Thibaut Maus de Rolley, ‘Putting the Devil on the Map: Demonology and Cosmography in the Renaissance,’ in Boundaries, Extents and Circulations: Space and Spatiality in Early Modern Natural Philosophy, eds. Koen Vermeir and Jonathan Regier (Dordrecht: Springer 2016), 179-207.

Jennifer Spinks, ‘The Southern Indian “Devil in Calicut” in Early Modern Northern Europe: Images, Texts and Objects in Motion,’ Journal of Early Modern History 18 (2014): 15-48.